Or, why falling off a horse was worse than falling off the wagon in 1852

We dare not trust the helm to Pierce,

Though in truth he were a Saint,

When conflicts dark their “front unfold,”

We fear that he might—faint.

—”Campaign Song for 1852″

In May of 2004, President George W. Bush crashed his mountain bike on mile sixteen of a seventeen-mile ride at his Crawford, Texas, ranch, suffering extensive abrasions to his face, knees, and right hand. Press coverage of this event, like similar awkward incidents (colliding with a Scottish police officer when on a bike in Scotland in July of 2005 at the G8 summit, choking on a pretzel and losing consciousness while watching football on TV in January of 2002), was of limited duration. Late-night comedians moved on to other topics fairly quickly. Even Bush’s enemies greeted news of these misfortunes with quizzical wonderment more than glee. Friend and foe of W. alike, it seems, agreed that any number of the president’s actions signified more about his character than his ability to stay on a bike or remain conscious after a freak accident.

Not so for Bush’s ancestor Franklin Pierce, America’s fourteenth president. (Barbara Bush is descended from a second cousin of Pierce.) Like Bush, Pierce lost consciousness after an accident, and like Bush, Pierce proved unable to remain upright on his nonmotorized transport. But antebellum Americans didn’t laugh these mishaps off. Two unfortunate days during the U.S.-Mexican War would haunt Pierce’s future political career and presidency, in the process revealing much about the meanings of manhood in the decade before the Civil War.

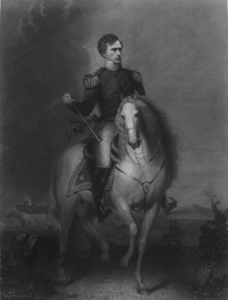

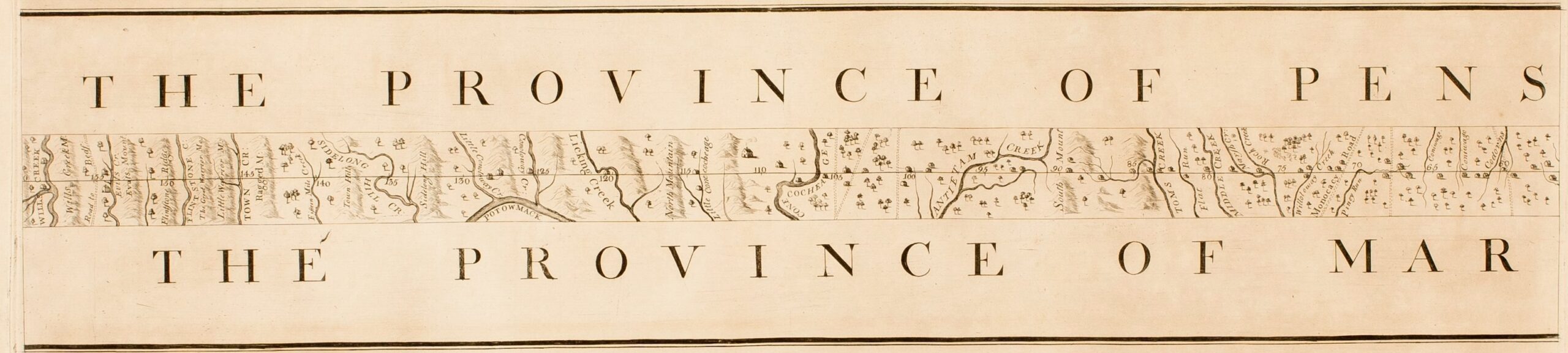

Pierce was a successful New Hampshire lawyer and former two-term U.S. Democratic representative and senator when Democrat James K. Polk provoked a war with Mexico in 1846. Like thousands of other Americans infused with the ideals of manifest destiny and convinced that Mexico deserved a “drubbing,” Pierce volunteered to serve in the war. He enlisted as a private but was promoted to colonel and then brigadier general (although he had no prior combat experience) because Polk was desperate for some officers without Whigish proclivities (the officer corps was as firmly Whig then as it appears to be Republican today). Pierce was part of the final dramatic campaign of the army, a two-hundred-mile trek under the direction of commanding general Winfield Scott from the port of Vera Cruz to Mexico City.

The army was nearing the capital when Pierce’s luck turned south. At the battle of Contreras on August 19, 1847, his horse reared, slamming Pierce into the pommel of his saddle. The resulting groin injury caused him to black out, and he fell from his horse, seriously injuring his knee in the process. His horse also stumbled and went down. Despite his injuries, Pierce somehow managed to mount another horse and fight through the evening, but the next morning, when leading troops into the battle of Churubusco, he twisted the injured knee on the uneven terrain, fainted again, and lay prostrate on the field until the end of the day.

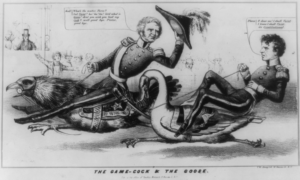

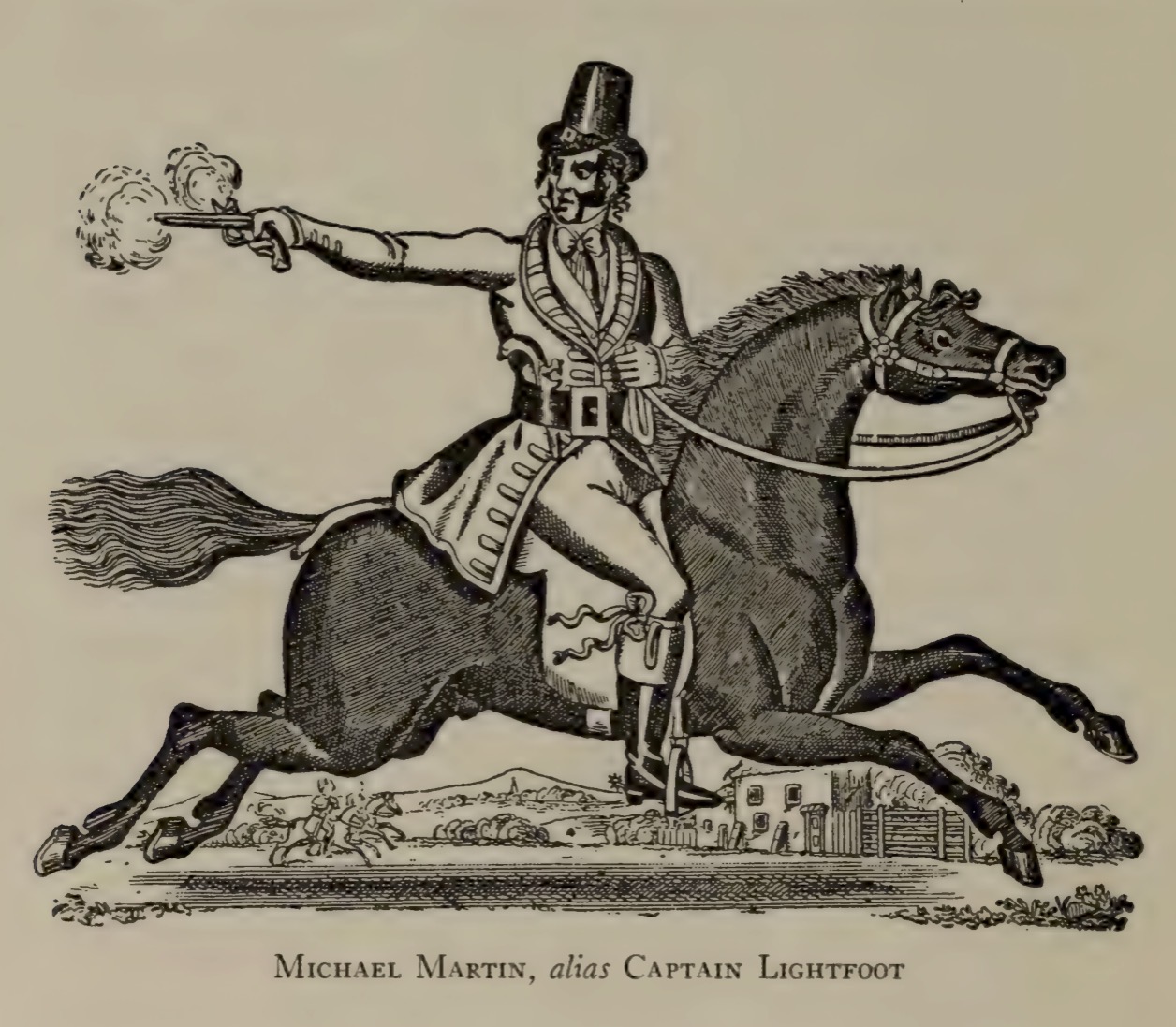

Pierce issued a forthright and detailed explanation for the mishaps, which received wide newspaper coverage. His commanding officers vindicated his behavior and made it clear that a series of unfortunate injuries had understandably and temporarily incapacitated an officer of greater than usual stamina. Pierce’s standing within the army doesn’t seem to have been hurt by the incident. Indeed, it was Pierce’s officer friends from the exclusive Aztec Club who first proposed his name for president in 1852. None the less, the fainting incident became one of the key issues of the 1852 presidential campaign, which pitted Pierce against his old commander, Whig nominee Winfield Scott, a man who never fell off his horse (fig. 1). The Richmond Whig was typical in casting its support of Scott in the context of Pierce’s Mexico misadventures. Pierce’s “known propensity for ‘fainting’ on the eve of great conflicts” tended “to demonstrate to the people that he is not the man for the crisis.”

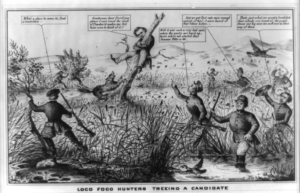

In an article titled “Presidential Qualifications” the New York Times focused primarily on the “alleged asphyxia, or fainting fit, which overtook Mr. Pierce at Contreras. It is highly important to know whether the fact is as rumor gives it. Did Mr. Pierce faint? Did he fall? And if so, why?” Was it “physical weakness” or “cowardice” that was “the cause of his being unhorsed”—or unmanned? “Not that weakness under such circumstances would be unpardonable,” the Times continued, somewhat insincerely, “considering that then, for the first time, the quiet country-lawyer stood face to face with horrid war; then first realized the nauseating smell of gunpowder; then first witnessed the struggle and the death of the soldier; and the profuse effusion of blood everywhere about him. We can very well understand, and understanding, forgive the momentary revulsion of nature at a scene so sickening, but coarser souls will make no allowances.”

The Democrats realized the importance of reassuring those “coarser souls” that Pierce was no coward. David W. Bartlett devoted an entire chapter of his 1852 campaign biography Life of General Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire to explaining Pierce’s fainting episode in Mexico, “because of the base attempt, on the part of some of his enemies, to traduce his military character.” In an attempt to put the literally below-the-belt accusations to rest, Bartlett quoted from eight separate testimonials, including General Scott’s official report, that the original fall was the fault of Pierce’s “restive” horse, that the battle was so strenuous that “many strong men fainted from sheer exhaustion,” and that two other general officers were not hurt as badly as Pierce but unlike Pierce, failed to continue fighting.