Pictures and their meanings in a Victorian home

Entering the Evergreens, the home of Austin and Susan Dickinson, the brother and sister-in-law of Emily Dickinson, is akin to experiencing an archaeological site. Members of the Dickinson family lived in the house continuously between 1857, when it was built, and 1943, when Austin and Susan’s daughter Martha died. Elements from the 1850s are still there today, along with other household objects and artwork chosen and arranged in subsequent years—creating, in effect, layers linked by networks of meanings and associations.

The Evergreens was home to a family whose members expressed themselves, their ideas, values, and feelings through furnishings, artwork, and household objects. Looking at photographs of nineteenth-century interiors and visiting historic houses like the Evergreens challenges us to explore the relationship between objects and their owners. While much has been written about how people interact with their material world and about how domestic objects were “expressions of sensibility,” I am particularly interested in understanding just how nineteenth-century Americans interacted with and assigned meaning to the growing body of images available for their consumption. Austin and Susan Dickinson’s home is an ideal place for this sort of inquiry.

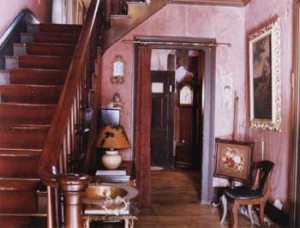

Austin Dickinson married Susan Gilbert in 1856 and moved into the Evergreens a year later. The house is next door to the Homestead, where Austin grew up and where his sister Emily lived and died. With Susan’s substantial dowry and Austin’s work as an attorney in his father’s firm, the couple could afford the finest art for their home. The couple’s selection and arrangement of artwork and decorative objects created a setting for hosting elegant parties and entertaining prominent visitors (fig. 1).

It was in the front hall and the parlor, interior spaces where visitors were welcomed, that these visitors first encountered the Dickinson’s good taste and proper values. So, for example, featured on the mantelpiece in the parlor was a reproduction of an eighteenth-century statue—Cupid and Psyche, by the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova (fig. 2). It was a work of art imbued with notions of love, devotion, and constancy and made popular by the contemporary mythologist Thomas Bullfinch. In Bullfinch’s words, “Jupiter handed Psyche a cup of ambrosia, and said, ‘Drink this, Psyche, and be immortal; nor shall Cupid ever break away from the knot in which he is tied, but these nuptials shall be perpetual.’ Thus Psyche became at last united to Cupid, and in due time they had a daughter born to them whose name was Pleasure.” The statue was a symbol of Austin and Susan’s love for each other, and its prominent placement on the mantel would have immediately registered with family, friends, and visitors. Other American families at that time displayed the statue on their piano, another centerpiece of the upper-middle-class home.

The Dickinsons installed their most prized paintings in the parlor (fig. 3). The room and its contents raise the question of who was actually placing the family’s artwork. We know that decisions about which household goods to purchase were shared by husbands and wives in middle-class households, but much work remains to be done to understand the various ways decisions were made concerning the arrangement of household furnishings once they were purchased.

When photographs of interiors are examined, it is not always easy to determine—strictly from the photograph—whether a man or a woman selected and arranged the pictures in the room.

We can get some clues from Susan’s 1895 inventory of furnishings, as well as the notations on the backs of the paintings in the Evergreens. These documents indicate that Austin and Susan shared a passion for art collecting. They began collecting paintings and other works of art by American artists of the Hudson River School including John Frederick Kensett and Sanford Gifford. They also collected European paintings from the Barbizon School of landscape painting as well as paintings of biblical, historical, and everyday life. Susan’s dowry enabled her to purchase landscape paintings in the early years of their marriage, but it was Austin who recklessly bought paintings year after year. He guiltily hid them in the guest bedroom, till he was ready to show off his extravagance to his wife and sister Emily. Martha recalled seeing her parents flushed and excited as they gazed on a new acquisition.

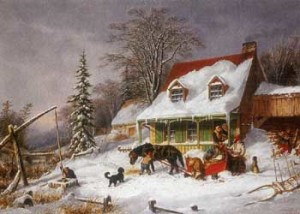

The Evergreens is an excellent site for studying the choices involved in picture collecting and display. There are approximately thirty paintings, fifty prints, several large framed photographs and photomechanical reproductions of artwork acquired by the Dickinsons. Beginning in the 1850s, tastemakers encouraged homeowners to create highly personal, eclectic arrangements of household furnishings, decorative artifacts, and visual images as a manifestation of refinement and personal taste. Such eclectic arrangements would give owners the freedom to effectively personalize art, by assembling it in such a way that it would evoke particularly meaningful family lore or memories of an inspiring trip abroad. This Victorian aesthetic also emphasized the value of owners’ distinct connection to individual works, suggesting that the narrative of owners’ relation to the work was more important than its particular aesthetic qualities. On their honeymoon in Canada, for instance, Austin and Susan purchased a small winter landscape—Country Farmhouse in Winter, painted in 1857 by Cornelius Krieghoff—that suggests the ideal family home life, in harmony with neighbors and animals (fig. 4). The scene encapsulated the belief that “the good picture . . . is either like a sermon teaching a great moral truth, or like a poem, idealizing some important aspect of life.” Catherine Beecher and other tastemakers recommended great works of art as visual lessons in history, values, deportment, and refinement, especially useful for families like the Dickinsons, whose art would be viewed by their own young children and visiting students from Amherst College.

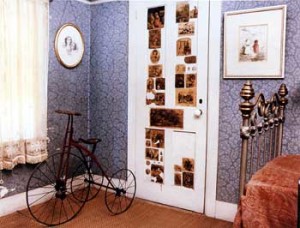

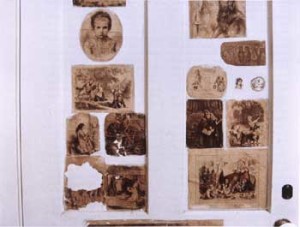

Austin and Susan encouraged their three children to study and enjoy visual culture ranging from fine works of art to pictures in family magazines. Their daughter Martha recalled going with her father to art galleries in New York City and Boston, marveling at his excitement in the presence of so many works of art. The three Dickinson children also spent time cutting pictures out of magazines and using these to decorate the doors of their bedrooms and the nursery (figs. 5 and 6).

While Austin and Susan impressed their guests with their art collection in the parlor, their children entertained their own guests upstairs in the nursery, where the backs of doors became the site for the children’s art gallery. That the house remained untouched for so many years is especially fortuitous, since it allows us to see rarely preserved children’s art. The nursery picture gallery in the Evergreens bears striking resemblance to the scrapbooks made during the period. This popular amateur art form coincided with the preference for clustering furniture, objects, and paintings into arrangements loaded with associations. Mass-produced handsome albums of blank pages provided flat surfaces comparable to blank walls on which the scrapbook creator could assemble and arrange personally selected collections of visual images together with mementoes of trips, special events, celebrations, and friendships. Cultural anthropologists have argued that assemblages of pictures in domestic installations—sometimes described as home altars—allow for the creation of a dream world or alternative visual environment from which the viewer can derive a complex web of meanings. The Dickinson’s art collection was an essential element in creating and maintaining their home as a sacred site for the cultivation of such meanings, particularly those associated with Victorian family values.

Austin, Susan, and their three children appeared to have had a wonderful life together until the 1880s. In that decade the youngest son, Gib, died at the age of eight, as did Austin’s father and sister Emily. In addition, Austin met Mrs. Mabel Loomis Todd, the wife of an Amherst professor, and the two began a passionate love affair, which lasted until Austin’s death in 1895. During these years, Austin’s interest in art collecting declined.

Meanwhile, Susan continued to collect art and decorate her home, maintaining as best she could some sense of normalcy. In 1885, she redecorated the front hall, perhaps hoping to convey a new message to family and visitors. At the center of that message would have been an impressively large biblical scene, Abram and Sara , painted by the Florentine Alessandro Cavazza in 1870 (fig. 7). Its placement was purposeful. On one level it was a sign of the family’s affluence, religiosity, and good taste, but the picture must have been much more than a symbol of upper-middle-class status. The painting depicts Genesis 12:10-20, in which the young Abraham and his wife Sarah are in Egypt, refugees from the famine then raging in their homeland of Canaan. The Pharaoh, according to the Bible passage, forced the beautiful Sarah to become his wife. Knowledgeable viewers would know that God then punished the Egyptian Pharaoh with a plague for failing to honor marital vows. The scene affirmed the sacredness of marriage vows, and its prominent placement in the front hall could stand as a warning against wayward intruders, such as Mrs. Todd, intent on disrupting families and breaking God’s law.

Susan made other selections informed by her dismay over her husband’s change of heart. She placed a large reproduction of a sixteenth-century painting—The Vision of St. Helena by Paolo Veronese (fig. 8)—on an easel in the northwest corner of the parlor, opposite the sculpture reproduction of Cupid and Psyche.

St. Helena’s mournful posture is in contrast to the romantic ecstasy of Cupid and Psyche. The subject, Helena, was spurned by her husband but respected by her son, the Roman Emperor Constantine, whom she converted to Christianity. The Veronese painting depicts the moment when, in her dream, the location of Christ’s holy cross in Jerusalem was revealed to her. Helena traveled to Jerusalem and brought a piece of the cross and the four nails back to Rome. While crossing the Adriatic Sea, the empress heard accounts of frequent drowning there. She was so strongly moved by the stories that she took one of the four crucifixion nails and threw it into the sea, and according to legend, the Adriatic Sea became peaceful. Christ’s sacrifice, symbolized by the nail, had the power to tame wild and violent things, making them gentle and docile. Perhaps St. Helena inspired Susan to believe she could tame her wild husband and bring him back to the perpetual love represented by Cupid and Psyche. How painful it must have been for the family to live together, passing in the hallways, hearing each other in their daily activities. How much worse it must have been to know that members of the small community of Amherst were aware of the unwed relationship in their midst and were watching Austin, Susan, and the Todds struggle to maintain the façade of family harmony.

After Austin’s death in 1895 Susan and her two remaining children continued to live in the Evergreens. They took several trips to Europe, where they purchased photographic reproductions of artistic masterpieces and important historical sites. As so many contemporary tastemakers suggested, these relatively cheap mementos could serve an important educational function by preparing the children for visits to museums and art exhibits. As they moved through the house, the Dickinsons could also see pictures that reminded them of European cathedrals or art masterpieces they may have visited. The stairway was a convenient location for groups of pictures whose meanings often intertwined (fig. 9). Susan and her daughter were particularly interested in religious works. In the Evergreens stair hall they hung photographs of European cathedrals next to a lithograph published by Sachse, after Raphael’s painting of St. Cecilia, and an engraved reproduction of an angel by Fra Angelico. The Dickinsons also brought back a painted reproduction of the central panel of Simone Martini’s Annunciation after seeing the original in the Uffizi in Florence. They placed it in the parlor, adjacent to Austin and Susan’s most treasured paintings.

Much as Susan and Austin had done, she and her daughter continued to arrange the family’s art according to personal associations and values rather than abstract aesthetic ideals. Such, as we have seen, was the advice of the Victorian era’s most important tastemakers. Hence, one hangs a view of the Bay of Amalfi near a reproduction of the Venus de Milo “because [the latter] came from those suns and skies of Southern Italy,” instructed Harriet Beecher Stowe in 1872.

Further Reading:

Information about tours of the Evergreens, as well as the home of Emily Dickinson, the Homestead, is available at the Website of the Emily Dickinson Museum. On the Dickinsons and their circle, see Jerome Liebling, The Dickinsons of Amherst (Hanover, N.H., 2001); Polly Longsworth, The World of Emily Dickinson: A Visual Biography (New York, 1990); Martha Dickinson Bianchi, The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson (New York, 1971); and Barton Levi St. Armand, Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul’s Society (Cambridge, 1984).

On household decoration see Kenneth L. Ames, “Meaning in Artifacts: Hall Furnishings in Victorian America,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 9 (Summer 1978): 19-46; Joan M. Seidl, “Consumers’ Choices: A Study of Household Furnishing, 1880-1920,” Minnesota History 48 (Spring 1983): 182-197; and Beverly Gordon, “Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age,” Winterthur Portfolio 31 (1996): 281-301. The phrase “expressions of sensibility” applied to material culture is from Katherine C. Grier, Culture and Comfort: People, Parlors, and Upholstery, 1850-1930 (Amherst, Mass., 1988).

For secondary sources about family life at home, see Clifford Edward Clark Jr., The American Family Home, 1800-1960 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1986) and David P. Handlin, The American Home: Architecture and Society, 1815-1915 (Boston, 1979).

For the story of Cupid and Psyche, see Thomas Bulfinch, The Age of Fable; or, Stories of Gods and Heroes (Boston, 1855; reprint ed., New York, 1998).

On arranging and viewing pictures at home, see Katharine Martinez, “At Home with Mona Lisa: Consumers and Commercial Visual Culture, 1880-1920,” in Patricia Johnston, ed., Seeing High and Low: Representing Social Conflict in American Visual Culture (Berkeley, 2006): 160-176; Susan Tucker, Katherine Ott, and Patricia P. Buckler, eds., The Scrapbook in American Life (Philadelphia, 2006); David Morgan, Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images (Berkeley, 1998); David Morgan, Protestants and Pictures: Religion, Visual Culture, and the Age of American Mass Production (New York, 1999).

This article originally appeared in issue 7.4 (April, 2007).

Katharine Martinez is the Herman and Joan Suit Librarian of the Fine Arts Library at Harvard University. She has a Ph.D. in American Studies from George Washington University; her essays on nineteenth-century American art and taste have appeared in several journals and books.