I.

I did not expect to find Samson Occom at the Mohegan Sun Casino–”300,000 square feet of gaming excitement”–in Uncasville, Connecticut. But there he was, an eighteenth-century Mohegan missionary, etched into the wall in one of the casino’s twenty-nine restaurants. I was hunched over a cup of clam chowder, trying to recover my senses from snow-blindness brought on by four days reading Occom’s archived manuscripts at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire, four hours north of Uncasville. Now, dining at the Mohegan Territory Diner, my bleariness was compounded by the overwhelming smell of cigarette smoke and the electronic din of slot machines. Lifting my eyes from my lunch, I glanced up at the giant reproduction of an 1861 reservation map plastered onto the wall. And there I spied a dot located just off the New London turnpike in the heart of the Mohegan Reservation: “Occom house.” How did Samson Occom get here?

Born in 1723, near Uncasville, Occom was raised by a traditional Mohegan family, before converting to Christianity during the Great Awakening and seeking a college-preparatory education from the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock. As an author, itinerant minister, fundraiser for Dartmouth College, tribal politician, and leader of an intertribal Christian separatist movement, Occom developed an indigenous brand of Christianity that promoted American Indian political independence and spiritual vitality during an era of rapid decline for many New England Indian communities. His archive of letters, journals, sermons, and hymns is the largest extant body of American Indian Anglophone writing from the colonial era. It documents the marginal, often fragile political and economic existence of American Indian communities in eighteenth-century New England and New York, as well as Occom’s struggle to support his wife Mary and their ten children.

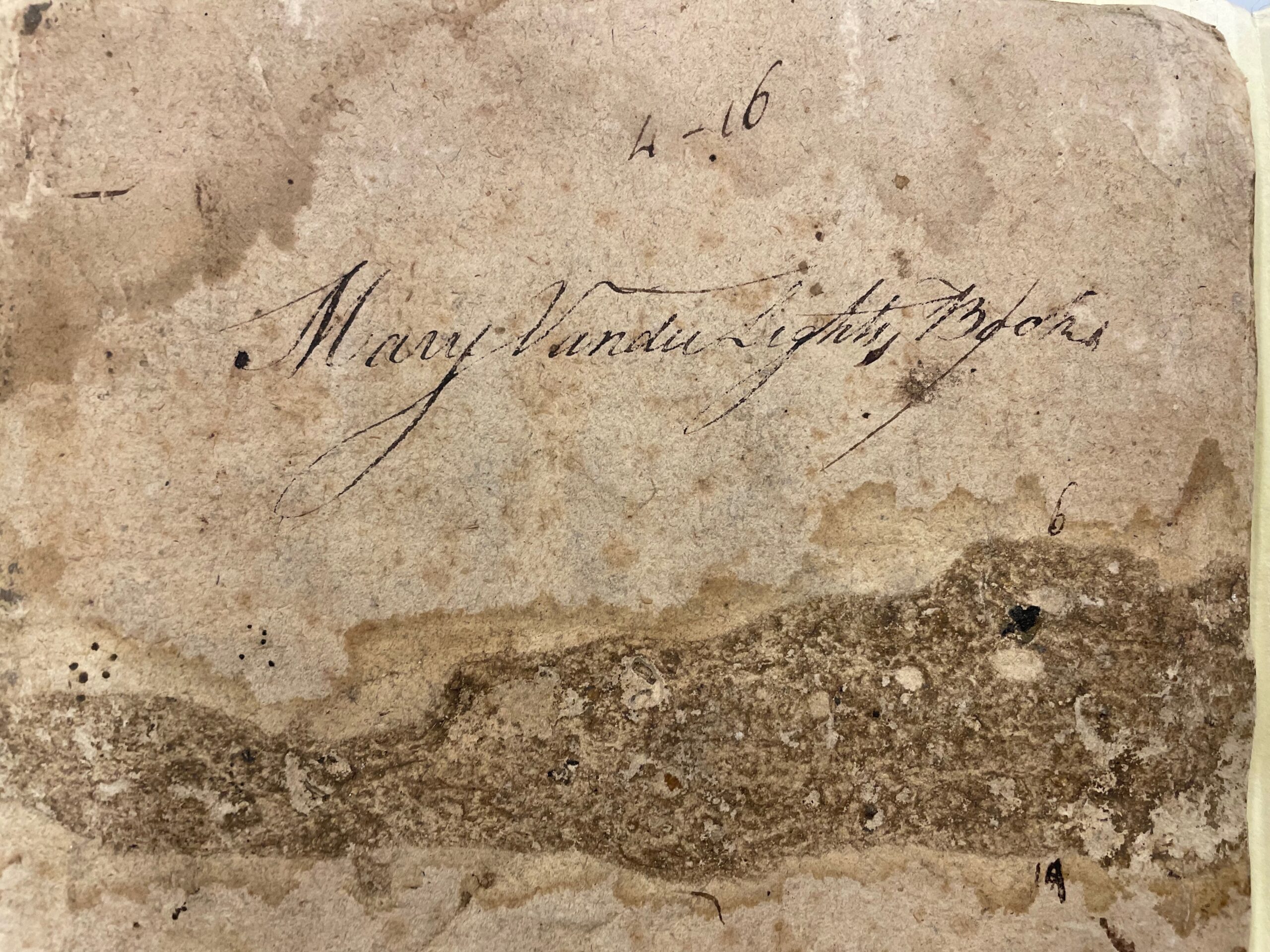

Occom’s writings communicate a deep sense of the hunger, wet, and cold that characterized subsistence living in early New England and New York, especially their impoverished American Indian communities. For four feverish days at Dartmouth, I followed Occom and his fellow Native missionaries as they argued in vain for fair pay from missionary societies, bargained endlessly with creditors, and struggled to maintain tribal land bases against predatory white tenants and speculators. To get by, Samson Occom carved bowls and bound books. He darned his own socks. He chased his only horse–an especially wayward mare–across pages and pages of marshes and wet fields, until he found her, legs broken, dead.

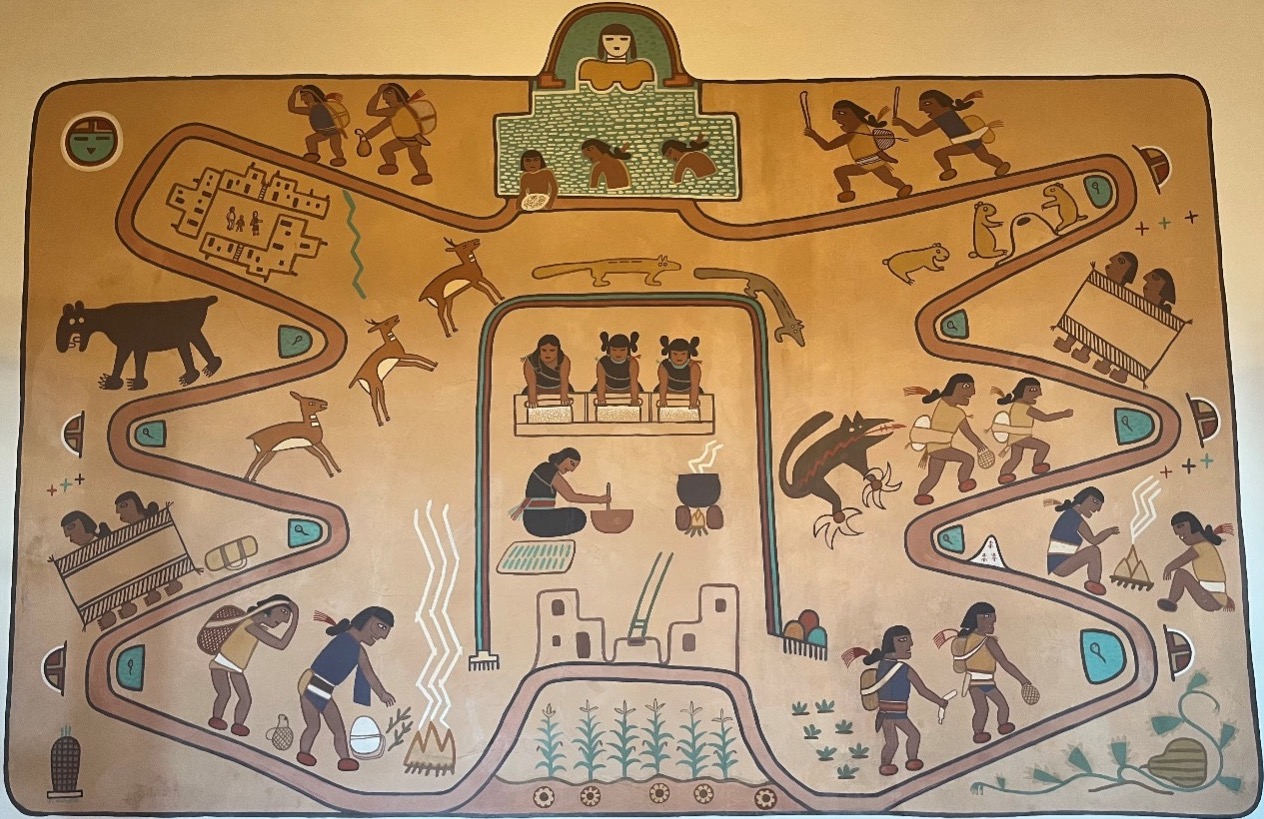

I left the Dartmouth archive saturated with a sense of the tenuousness of Mohegan life in eighteenth-century New England. A few hours later, I arrived for the first time at the Mohegan Sun Casino complex. I parked my rental car in the six-story “Indian Summer” garage, then walked the path circling the perimeter of the “Casino of the Earth” in simple astonishment. I have visited tribal casinos in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, but none of them compare to the Mohegan Sun: its arching domes glittering with stars, shielded by giant banshells painted with tribal designs; the casino itself mapped on a four-directions, four-seasons axis; thirteen seasonal moons marking its circular perimeter; corn, squash, and beans “Three Sisters” designs woven into the carpet; frame longhouse and Indian stockades straddling casino entrances; animatronic wolves perched on stone outlooks hovering over the “Wolf Den” gaming area; and Pendleton-blanket covered chairs in the diners.

As I lapped the Casino of the Earth, I laughed out loud marveling at the strange twists of history. I am an early American literary historian. I descend from the Puritans, but I tend to root for the Indians. I like texts thick with ironic signifying and secret codes, texts that fold history back on itself. I did not expect to find Samson Occom at the Mohegan Sun, but I should not have been surprised. Native Americans in New England have always had to contend with colonial expectations of what Indianness should look like. Their livelihoods have often depended on it. The Mohegan Sun Casino is a brilliant, unsettling monument to this long historical negotiation.

II.

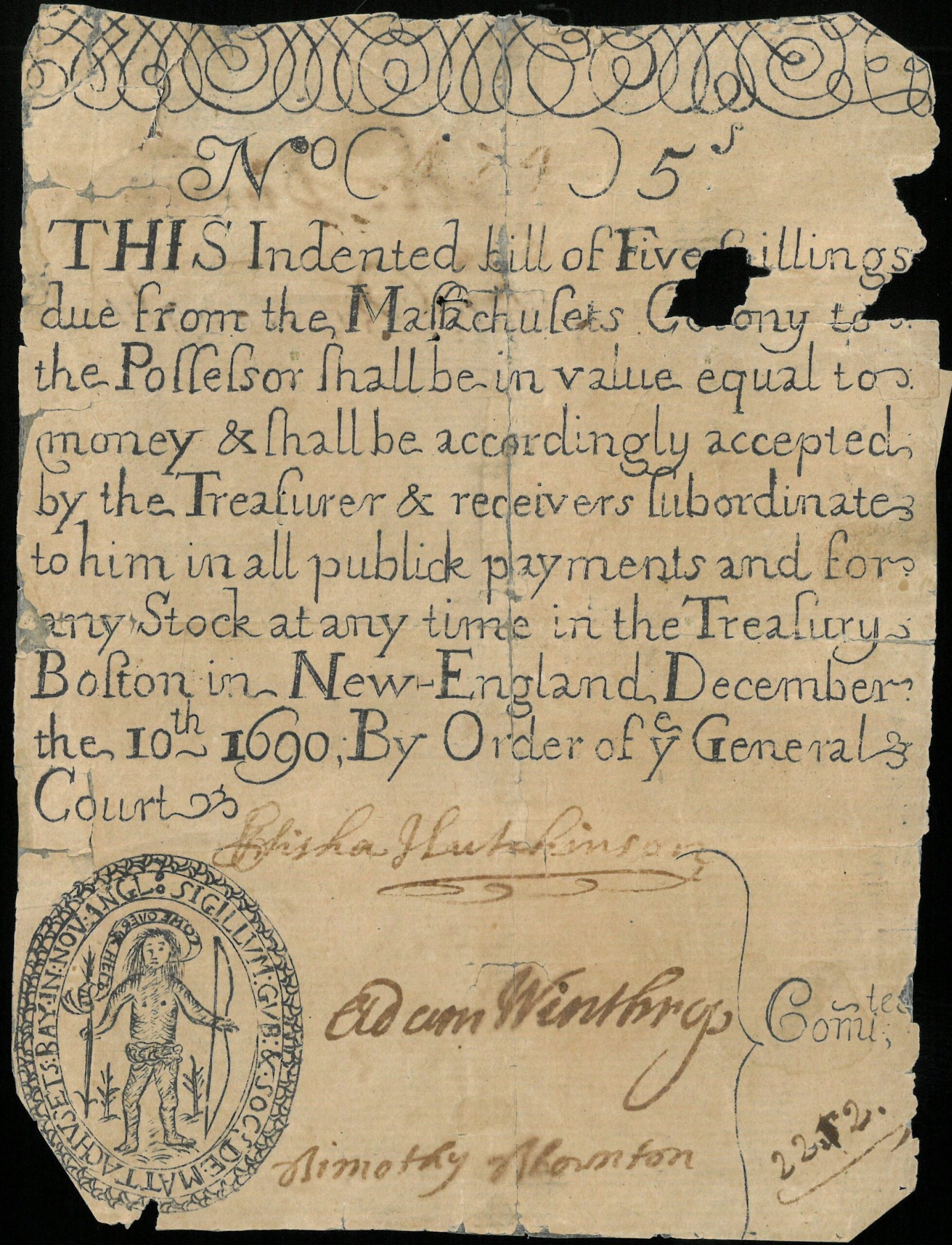

Money troubles followed Samson Occom his entire writing life. His first letter dates from 1752, when Occom was stationed as a schoolmaster among the Montauk tribe on Long Island. He wrote, “I have not Receiv’d a peney from the Gentlemen at Boston . . . and I am now Driven to the want, almost, of every thing.” During the early years of his career, when he was employed by religious societies, Occom typically received a fraction of what was paid white missionaries. “Now You See What difference they made between me and other Missionaries,” Occom would later remark. “They gave me 180 Pounds for 12 years Service, which they gave for one years Service in another Mission– . . . what can be the Reason? . . . I believe it is because I am [a] poor Indian.”

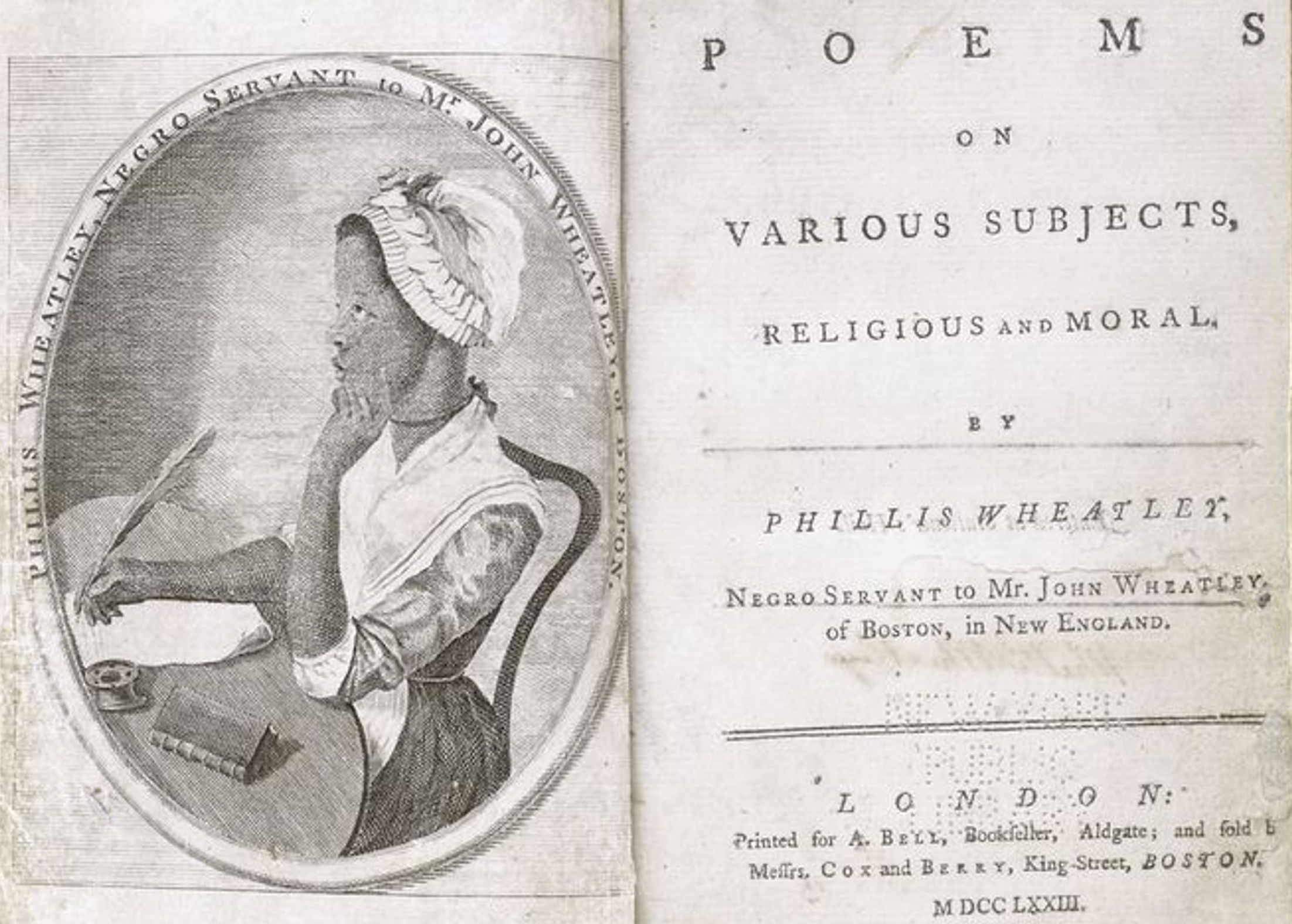

From 1765 to 1768, Occom traveled to England as a fundraiser for Moor’s Indian Charity School, an educational experiment designed by the Yale-educated New Light minister Eleazar Wheelock to train Native missionaries. Throughout his tour, Occom was ogled, scrutinized, mocked, misrepresented, interrogated, and exoticized. Wheelock’s American rivals accused Occom of imposture, declaring it impossible that in one generation a traditional Mohegan could become an ordained minister. Occom wrote to Wheelock in 1765, “They further affirm, I was bro’t up Regularly and a Christian all my Days, Some Say, I cant Talk Indian, others Say I Cant read.” Despite these indignities, Occom managed to raise thirteen thousand pounds. “I was quite Willing to become a Gazing Stock, Yea Even a Laughing Stock, in Strange Countries to Promote your Cause,” he remembered bitterly in a letter to Wheelock. Wheelock soon phased out admissions of Native American students and moved Moor’s Indian Charity School to Hanover, New Hampshire. It became Dartmouth College.

In 1768, Occom composed a short autobiographical narrative, in the hopes that he could once and for all establish his identity on his own terms. “Having Seen and heard Several Representations, in England and Scotland, made by Some gentlemen in America, Concerning me, and finding many gross Mistakes in their Account,—I thought it my Duty to give a Short Plain and Honest Account of myself, that those who may hereafter see it, may know the Truth Concerning me.” Occom affirmed that he had been brought up a “Heathen,” in “Heathenism,” choosing words that squared with his white audiences’ vocabularies and expectations. He included ethnographic details that also satisfied his readers’ notions of the cultural distinctions that supposedly separated American Indians from Europeans: “Neither did we Cultivate our Land, nor kept any Sort of Creatures except Dogs, Which We Used in Hunting; and Dwelt in Wigwams, These are a Sort of Tents, Coverd with Matts, made of Flags.” A few paragraphs later, Occom repeated this autoethnographic detail, describing his home at Montauk, Long Island, in the 1760s: “I Dwelt in a Wigwam, a Small Hutt fraimed with Small Poles and Coverd with Matts made of Flags.” The repetition is revealing. When he wrote this narrative in 1768, Occom was living in a wood-frame house in Uncasville. But he knew that the English colonial imagination coded wigwams, not frame houses, as Indian, and proving his identity and defending his integrity meant satisfying to some extent the English colonial imagination of Indianness.

III.

Just as Samson Occom had to prove he was really “Indian” in terms familiar and comfortable to his English and Anglo-American audiences, American Indians today are often called upon to answer non-Indian expectations about how “real” Indians should look and act. This points to an abiding paradox at the heart of American Indian tribal sovereignty: in order to access federal resources and enact certain forms of institutional self-governance, tribes must win “recognition” from the federal government. The enactment of self-determination in the public sphere is also mediated by dominant cultural expectations of Indianness. Tribal gaming has been so controversial in part because it challenges romantic notions of Native Americans as essentially precapitalist peoples.

Reaction to Indian gaming has been especially fierce in the state of Connecticut, home to both the Mohegan Sun and the Mashantucket Pequot Foxwoods casinos. Tribal gaming opponents in that state and elsewhere have challenged the legitimacy of American Indian tribes and of the federal recognition processes through which these tribes have won the right to operate casinos on reservation lands. Twenty Connecticut communities petitioned for a moratorium on tribal recognition in May 2001. They charged that opportunistic self-proclaimed “Indians” were bamboozling the federal government into granting them recognition.

Among American Indian tribes, winning federal recognition is not viewed as an easy prospect. It can be a costly and difficult process. It requires that tribes document hundreds of years of continuous tribal self-governance, continuous occupation of traditional tribal lands, and continuous observance of cultural practices. Colonial conditions including war, impoverishment, political upheaval, and removal have made mustering this kind of documentation exceedingly difficult if not impossible. In fact, the survival of some tribal communities, traditional governments, and cultural practices has historically depended upon the evasion of colonial surveillance and government documentation and regulation.

During the eighteenth century, colonial overseers purposefully disrupted the traditional Mohegan tribal sachemship that had long resided with the Uncas family. In protest, Samson Occom and his generation founded separatist Indian Christian churches as spaces for community self-governance and self-determination. Occom led many Christian Mohegans away from Connecticut in 1785, to join with other Christian southern New England tribal members in exodus to Brotherton, New York. His sister Lucy Occom Tantaquidgeon did not make the journey. Instead, she stayed home in Uncasville and assumed a leadership role in tribal affairs. Historians have observed that what happened at Mohegan also happened among the Choctaw, Creek, and other Removal-era tribal communities: female-headed tribal factions tended to resist removal from traditional lands, even when it cost them formal recognition from the federal government; male-headed tribal factions developed male-focused tribal governance and land ownership systems recognized as legitimate by federal Indian overseers and broader Euro-American society.

In 1831, during the Jacksonian era of Indian Removal, Lucy Occom Tantaquidgeon, her daughter Lucy Tantaquidgeon Teecomwas, and her granddaughter Cynthia Teecomas Hoscoat deeded a plot of land on Mohegan Hill to tribal ownership for the building of a community church. These women understood that it would be strategically important to the continuance of the Mohegan on traditional lands to escape removal by demonstrating themselves a “Christianized” people. The Mohegan Congregational Church has remained a key venue of tribal political, social, and cultural life ever since. Even when tribal treaty relationships with the federal government were terminated in 1860s and 1870s, the traditional matrilineal tribal leadership remained intact through the church’s Ladies Sewing Society. The half-acre on which the church stands is the only plot of land that remained continuously in tribal ownership. Proving their ownership of that plot of land and proving the female line of leadership that began with Lucy Occom was critical to the Mohegan tribe’s successful petition for reinstatement of federal recognition in 1994.

American Indian tribes must document continuous histories in order to win federally recognized powers of self-determination that make casino gaming possible. Now, casinos are funding initiatives to restore and continue tribal cultural and historical traditions. The Mashantucket Pequots have devoted Foxwoods revenues to the construction and maintenance of an enviable museum, library, and archive—employing at least one full-time manuscript archivist—on the grounds of the tribal complex. The Mohegans are also invested in preserving and perpetuating their culture. “Aquay / Greetings, Welcome to the Mohegan Indian Reservation. Mundo Wigo [The Creator is Good],” read the green road signs at the tribal reservation boundaries. With gaming revenues, they undertook a million-dollar restoration of the aging and fragile Mohegan Congregational Church in 2003. Without the Mohegan Congregational Church, there would probably be no Mohegan Sun Casino; without revenues from the Mohegan Sun Casino, the church might not be standing today. The beautifully restored white clapboard structure stands about a mile down the road from the Mohegan Sun. The tribe also maintains a park and burial grounds at Shantok on the bluff overlooking the Thames River. Signs provide park information and regulations in both English and Mohegan languages. Riverside trails are littered with crushed clam shells, a reminder of the aquacultural practices at the heart of traditional Mohegan life, practices that were interrupted by colonial incursion and that are being revived—thanks to gaming revenue—in tribal oyster and clam farms in Long Island Sound and area rivers.

History is also built into the Mohegan Sun Casino. It is an exceptionally smart space, one designed to both confirm and redirect our ideas of New England Indian life and history. There are, of course, the hyperreal mobilizations of the familiarly iconic “Indian,” designed to establish once and for all, beyond the question of federal recognition, beyond the interrogation of gaming critics, that the Mohegans are indeed an American Indian tribe. But there are also more subtle and profound memorializations of Mohegan tribal history. The casino houses an unassuming life-size statue of legendary modern Mohegan medicine woman and anthropologist Gladys Tantaquidgeon (1899-present). Fidelia’s Restaurant (located next door to Michael Jordan’s Steak House) is named after Fidelia Hoscott Fielding (1827-1908), the last fluent speaker of Mohegan dialect and an honored traditional culture keeper. The Hall of the Lost Tribes—a smoke-free gaming room—features the marks of sachems of thirteen extinct Connecticut Indian tribes culled from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century documents. And there on the wall of the Mohegan Territory coffee shop, Samson Occom’s home site appears in a wall-sized 1861 map of the reservation.

IV.

Within the last decade, the emergence of tribal casinos has changed the American landscape and challenged how we have become accustomed to thinking about American Indian communities. Casinos spatially demarcate sovereign American Indian political domains within the United States. They materialize the new political and economic power of tribal communities assumed long gone. No doubt this is why so many Americans find them unsettling.

Even people who know a bit about American Indian history and who support tribal sovereignty as an abstract principle find themselves troubled by tribal casinos, especially ones as spectacular as Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun. It can be difficult to reconcile these contemporary manifestations of New England Native American life with our historical imaginations, or to rectify our sense of what tribal sovereignty ought to mean with the ways living Native peoples actually decide to exercise self-determination. The cognitive distance between archives and casinos seems almost impassable.

But finding Samson Occom at the Mohegan Sun proves an exceptionally astute historical intelligence at work in casino design: the Mohegan have designed their casino to reflect public fantasies about Indians while maintaining their own tribal history. It is possible, then, to see the Mohegan Sun Casino as a renegotiation of practices of cultural commemoration, a reconfiguration of the intersection of historical time with contemporary space. Tribal casinos teach us what Samson Occom and other Native peoples in colonial times knew all too well: how chancy and random the turns of history can be, how strange and unimaginable its forms and outcomes.

Further Reading:

For more on Indian Casinos, Samson Occom, and the Mohegan, see David Kamper and Angela Mullis, eds., Indian Gaming: Who Wins? (Los Angeles, 2000); William DeLoss Love, Samson Occom and the Christian Indians of New England (reprint Syracuse, 2000); Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel, Medicine Trail: The Life and Lessons of Gladys Tantaquidgeon (Tucson, 2000).

This article originally appeared in issue 4.4 (July, 2004).

Joanna Brooks is assistant professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin and author of American Lazarus: Religion and the Rise of African-American and Native American Literatures (Oxford, 2003).