As I write this column, I gaze upon my poolside deck contemplating the various rituals to be undertaken there on Labor Day (which will have passed by the time you read this). What manner of meat shall I burn on the Weber? Will my son refuse sunscreen? Will my six-year-old daughter once again defy all reason and insist that the baseball Cubs, who have drawn her father from poolside to Sony-side, are in fact baby bears? Will my wife begin to doubt the professed irony with which I excuse my interest in whatever Nascar race happens to be on TV (Ricky Bobby . . . I love you, man!!)? Will we all make our way through the day with the knowledge that, in Florida, Labor Day is even more meaningless than elsewhere in the country? Here, it marks no beginnings—school begins in mid-August. And it marks no endings—summer for us lasts at least another two months, depending on whether or not you consider an average daily temperature of eighty-eight degrees true “fall weather.”

The fact that most Americans pay tribute to labor with leisure is not terribly surprising. Even on what are supposed to be somber holidays—Memorial Day and Martin Luther King Day, for example—most people watch sports or go shopping or do something recreational. Few of us use holidays for what the politicians intended when they established them. But never mind all that. Nobody will be surprised to learn that it takes a lot more than an act of Congress to bring Americans off the national sofa.

As a columnist, however, it is my solemn duty to address the obvious and to compel you, dear reader, to smirk, giggle, and perhaps even raise a clenched fist in outrage.

So let me return to Labor Day. What are we to make of a holiday intended to pay tribute (according to the U.S. Department of Labor Website) “to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of our country”? Who among us—even those who actually labor for a living—ever ponders just what form such a tribute should take? Part of the problem may simply be that few of us these days have any idea of exactly who’s receiving our tribute. Who in fact are those “workers” we memorialize as we throw another hot dog on the barbeque?

Judging from the origins of the holiday, they are not salaried workers. The founders of Labor Day were one or another nineteenth-century labor organizer named McGuire. Peter had been general secretary of the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners; Matthew was secretary for the Paterson, New Jersey, local of the International Association of Machinists. From the early 1880s the holiday took hold in the industrialized states, and then in 1894, the same year he sent federal troops to break the Pullman Strike, President Cleveland signed legislation declaring the first Monday in September an official holiday in the District of Columbia and the Territories.

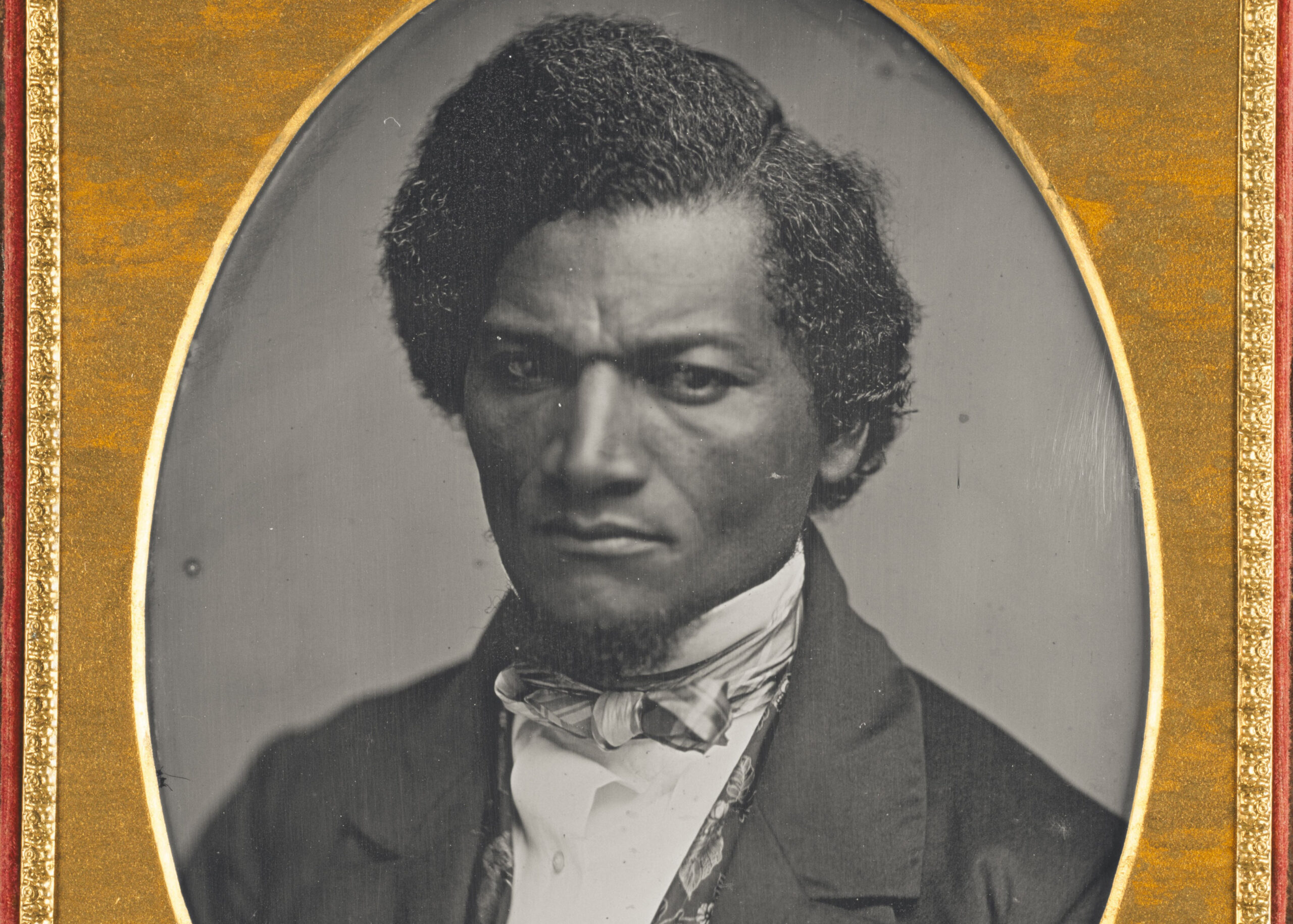

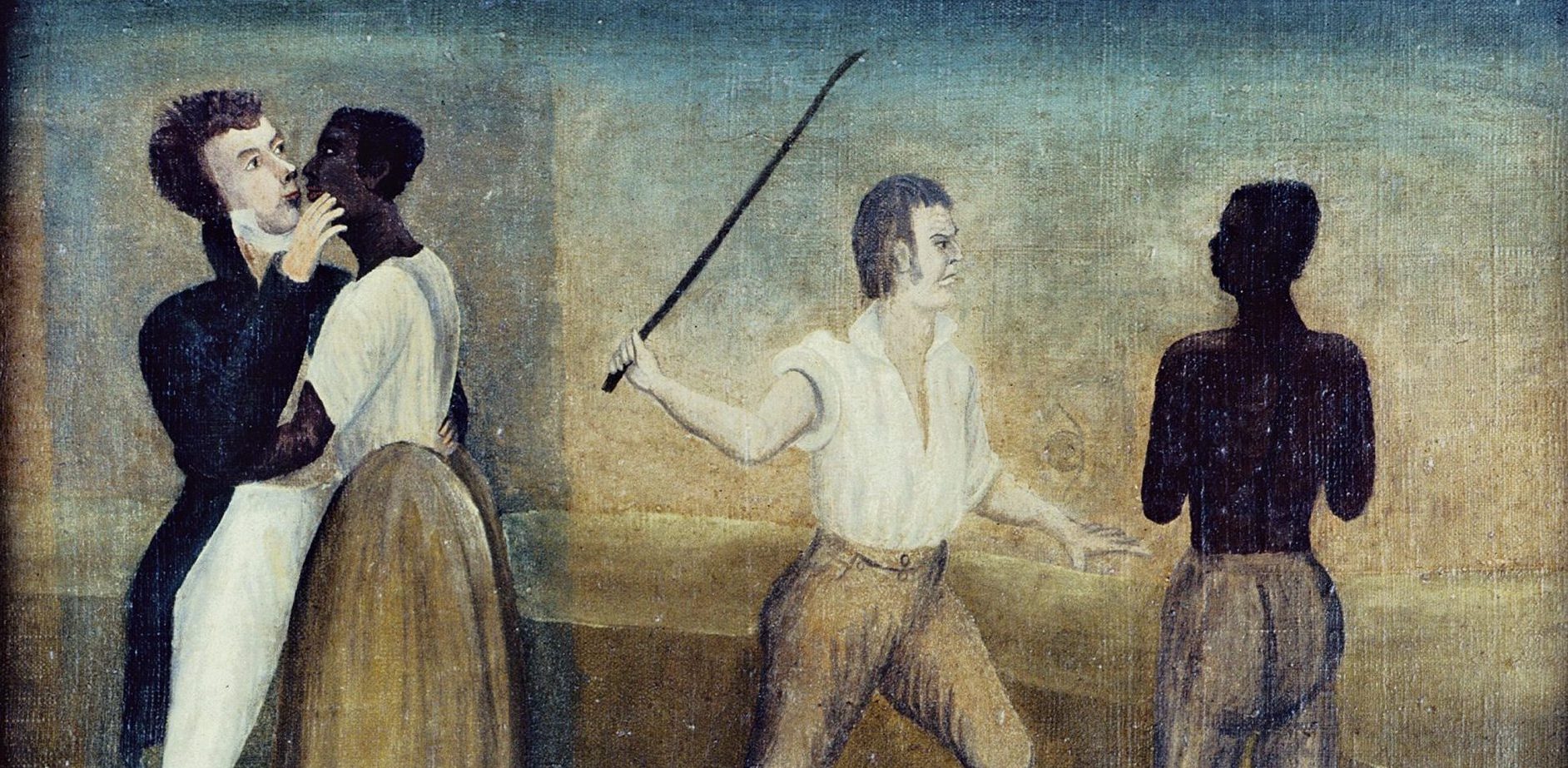

So the workers for whom the holiday was founded were principally industrial workers—battered and literally beaten by American industry. The purpose of the holiday was not simply to give workers a much-needed break from the endless twelve-hour tedium of factory work. It was, in the view of its organizers, a way for workers to reveal their political potency. Hidden away in the crevices of industry or the working-class ghettos of American cities, the laboring hordes were easily ignored by politicians. It took good Samaritans with the missionary zeal of Jane Addams to find them and do the hard work of transforming them into citizens. Perhaps a day dedicated to laboring people, a day of parades and picnics and other happy occasions, would be an efficient way for labor to rear its head.

Organizers faced an uphill battle. For the holiday to have its desired effect, it had to be broadly observed. A special day in New York City would have little effect on the consciousness of national political parties. But a national holiday would need the support not only of state and national politicians but also of employers. The early laws and ordinances endorsing Labor Day carried no legally binding requirement of observance in the private sector. If your boss wanted to keep you working, he was free to do so (and still is, assuming he doesn’t work for the government). Organizers also faced the extraordinarily difficult problem of persuading the xenophobic American middle class that the face of labor was neither the corrupt Irish drunk nor the bomb-throwing central European anarchist.

That is why, in its heyday, the celebrations of Labor Day were as polite and decorous as a Victorian tea party. Parade and picnic banners were more likely to feature patriotic proclamations than the radical slogans of the Industrial Workers of the World.

By the early twentieth century, labor organizers were discovering that few workers were inclined to spend their holidays in carefully circumscribed public demonstrations—not because they craved more radical fare but because they too sought a piece of the great American leisure pie. Hence, in some cities, labor picnics became spectacular affairs, sometimes held at beaches or amusement parks and featuring baseball games, boxing matches, bicycle races, strength and beauty contests, as well assorted contests testing the skills of tradespeople. The industrial workforce—or at least the industrial workforce the holiday put on display—was every bit as leisure loving as the rest of America.

The delicate act that Labor Day used to be—a political act but also a patriotic and American act—explains why it is that we pay tribute to workers in September and the rest of the world does so on May 1. Our workers are Americans first, workers and laborers second. As if that point had not been amply demonstrated by, say, workers’ performance in World War II, we took a firm stand against worker internationalism when President Eisenhower declared May 1 National Loyalty Day. As President Bush put it not long ago in his own strange twist on what might better be called “Red Scare Day,” the first of May is a day to “reaffirm our allegiance to our country and resolve to uphold the vision of our Forefathers.”

The days when respectable Americans worried that lurking behind the walls of every union hall was some manner of conspiring foreign radical are thankfully gone. Nobody feels safer anymore because four months separate our labor day from the rest of the world’s. And while we still have our civil Labor Day parades, the shrinking industrial workforce and the blurring social and ethnic boundaries between the underpaid, indebted middle class and the underpaid, indebted working class have made the working class even less visible. Democrats still pay lip service to labor, but it’s with the soccer moms and Nascar dads (oh dear God . . . that’s me!!) that they believe their bread is truly buttered. We don’t even have that vestige of working-class activism, the “Labor Party.” It exists in Britain, Israel, and elsewhere in the industrialized world, but in America no political party has ever wanted to stand up and declare itself the party of labor—except perhaps the socialists, and we know where that’s gotten them.

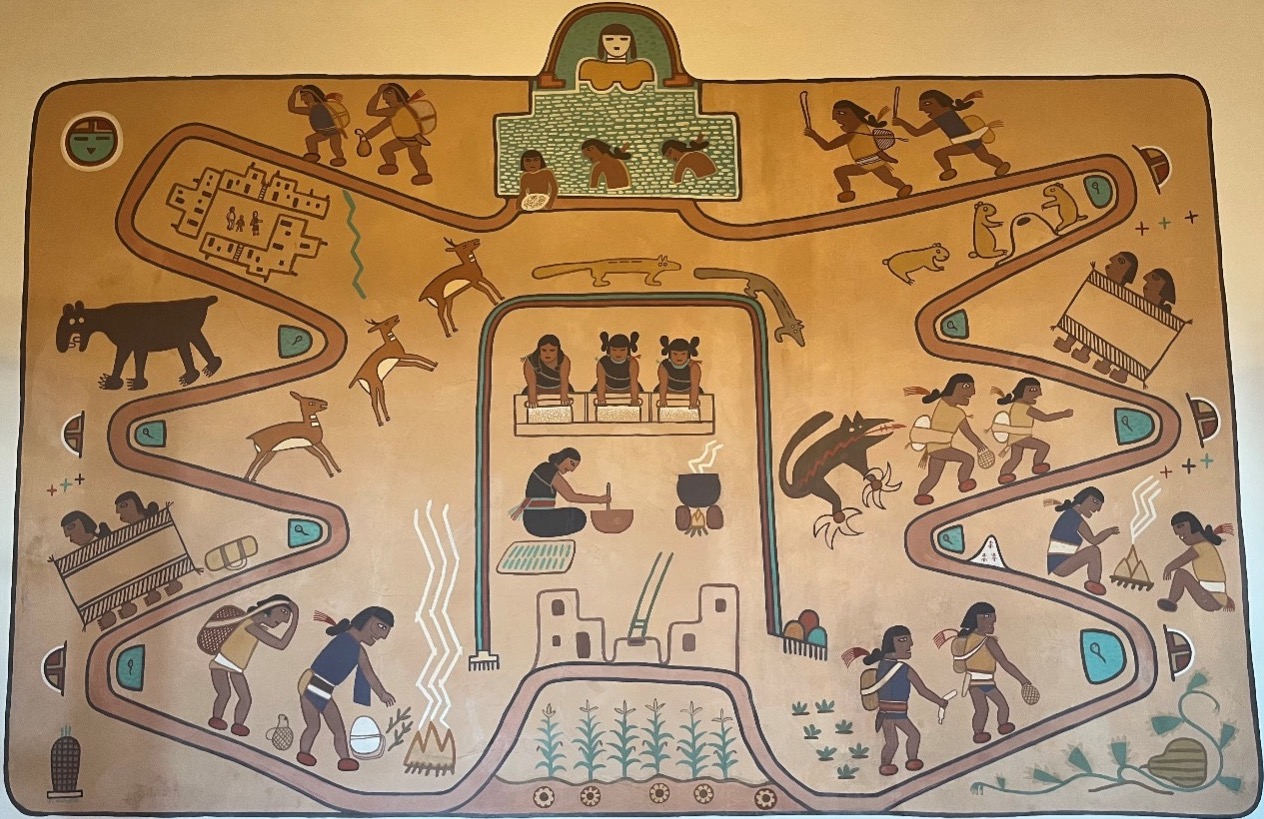

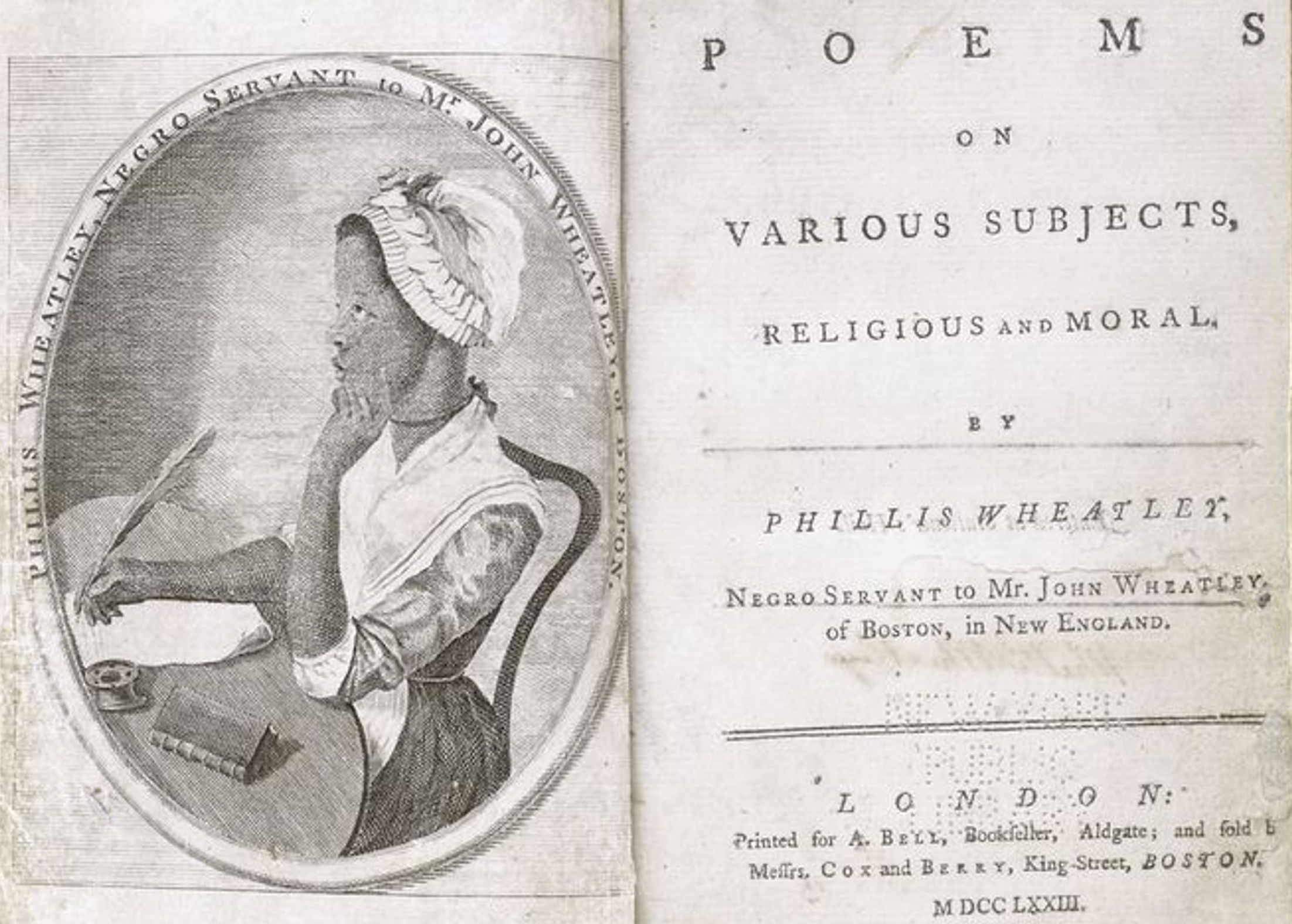

America’s ambivalence about labor is nothing new. In the colonial era the ruling class had nothing but contempt for anything that could be justly called “work.” An eighteenth-century American gentleman went to great pains to demonstrate to the world that he did not labor with his hands. His painted portrait featured, in the very center of the frame and beneath that carefully quaffed periwig, those delicate, feminine hands, unsoiled by any manner of toil, usually clasping a philosophical treatise or quill pen. The founders of the Jamestown colony died in droves in part because they were unable to enslave the supposedly docile Native population that was to do all the hard work of building a colony—work that they themselves, young gentleman that they were, had no intention of doing.

Benjamin Franklin, that apostle of the modern American work ethic, was so dedicated to hard work that at age forty-two he retired from the printing business to pursue a gentleman’s life of public service and philosophical inquiry.

In early America, the point is, there was little dignity in labor. The very definition of the term carried with it almost no positive connotations. According to the eighteenth-century English lexicographer Samuel Johnson, labor was simply “the act of doing what requires a painful exertion of strength, or wearisome perseverance; pains; toil; travail; work.” Hence, one of its definitions was that most undignified of early modern experiences: childbirth, which Johnson also defined as “travail.” For Johnson and his ilk there was no romance, no soul-purifying catharsis in hard physical work. It was simply another form of misery the unwashed, impoverished hordes could not escape.

“Labour for labour’s sake,” John Locke observed, “is against nature.” If you were fortunate enough to have the option not to labor, you would defy the very laws of nature—those rules of motion that bound the natural, physical, social, and psychological worlds into one seamless, well-functioning whole—by voluntarily enduring sweat and toil. It was the rare iconoclast who imagined the leisure class becoming the sweaty class. “Those who are not obliged to labour by the condition in which they were born,” wrote the early eighteenth-century English essayist and playwright Joseph Addison, “are more miserable than the rest of mankind, unless they indulge themselves in that voluntary labour which goes by the name of exercise.”

We’ve come a long way. Never mind the romanticizing of labor by social realist artists and folkies in the last century. Now we have presidents appearing on their “ranch,” swinging axes and whacking bushes. One thing’s for sure, you would never have seen George Washington or Thomas Jefferson hoeing a row.

So where does this leave those of us who do not actually “work” for a living, in the sense understood by the founders of Labor Day? What of the vast libertariat out there that makes its living behind computer screens and in air-conditioned offices and that scoffs at the hypocrisy of our blue-blood leaders sweating through their expensive western apparel? What do we do with Labor Day? How are we to pay tribute to the people who actually do sweat their way through a work day? Go to parades and admire working people from afar? I myself do a version of this anyway. When they replace a water main on my street, I’m out there yakking away with the public works guys.

Maybe the best way for the non-laboring to pay tribute to the laboring is to lay around by the pool and reflect on the fact that this is not, for a change, our day. This is somebody else’s day, and we should let them have it. Or maybe the thing to do is take this day as an opportunity to reflect on exactly what it is we do do. In the immortal words of Kurt Vonnegut, “we are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you any different.”

Further Reading:

Michael Kazin and Steven J. Ross, “America’s Labor Day: The Dilemma of a Worker’s Celebration,” The Journal of American History, vol. 78: 4 (March, 1992): 1294-1323. And Keith Thomas, ed., The Oxford Book of Work (New York, 1999). Also, on the history of Labor Day, see the Department of Labor Website. The Vonnegut quote is from a marvelous 1994 interview that originally appeared in Inc. Technology. The interview can be viewed at the Vonnegut Web.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.1 (October, 2006).

Edward Gray is associate professor of history at Florida State University and editor of Common-place.